Fusion voting has gotten a fair amount of notice in recent months as new centrist political parties in New Jersey and Michigan have each announced intentions to overturn their state’s ban on fusion as an unconstitutional abridgment of fundamental political rights.

Fusion voting was once legal and common in the United States, but today it is generally unknown or, even more commonly, misunderstood. Specifically, two very different forms of balloting, with very different consequences for minor parties and their members’ associational rights, are often not distinguished. They should be.

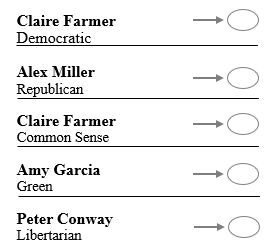

A “fusion voting” regime is one in which more than one political party can show its support of a candidate on its own ballot line, with votes cast on that line added to votes on other nominating parties’ lines to produce the candidate’s final total. In the hypothetical below, for example, Claire Farmer appears not only on the Democratic Party line but also on the Common Sense Party’s one.

FIGURE 1: “DISAGGREGATED” FUSION BALLOT ILLUSTRATION:

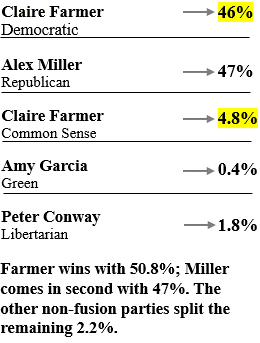

The importance of this line separation is shown by the figure below, where the votes of supporters of the Common Sense explained her win. That’s a pretty good bargaining chip for the Common Sense candidate when she takes office.

FIGURE 2: Farmer Wins, But only with Common Sense Support

A Short History

Fusion voting was used sporadically in the pre-Civil War era, most prominently by political abolitionists determined to emphasize their opposition to slavery. But it was after the Civil War that fusion parties bloomed across the nation.[1] Democrat-Populist fusion was common in the north, as wage earners and farmers united against Gilded Age Republicans. In the south, fusion allowed newly enfranchised Black males to unite with poor white farmers in Republican-Populist fusion tickets. In a few southern states such unity actually elected governors and members of Congress, but this multi-racial unity did not survive the rise of Klan terror and Jim Crow segregation.

Throughout the 19th century, then, minor parties were able to choose between running stand-alone candidates or backing fusion candidates in coalition with another party. The latter strategy proved the more potent one, with minor parties deriving much of their power from the vote share that they were able to concretely demonstrate via fusion.

In the waning years of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, however, the two major parties accumulated enough power to ban fusion in nearly every state. Minor parties did not disappear, but they were no longer able to escape the spoiler or wasted vote dilemma that plagues third parties in our single-member district system. Once fusion was banned, third-party supporters who wished to vote for a viable candidate had no choice but to abandon their prior loyalty and instead associate with one of the two major parties. The major parties essentially used – some might say abused – the power of the state to consolidate their grasp on power and policy-making.

Today, traditional fusion remains legal and common only in Connecticut and New York. In those states, members of minor parties continue to enjoy the right to choose their own standard-bearer, even if that candidate enjoys the support of a bigger, better-known party. In so doing, minor-party voters are able to vote for the candidate they prefer under a party label that better reflects their values. The fusion parties can also run stand-alone candidates, but most commonly fuse with one or another of the major parties.

Confusion?

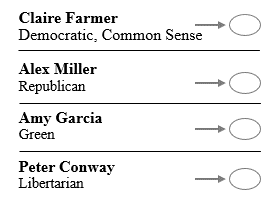

A related but qualitatively different system – sometimes confusingly referred to as “aggregated” fusion – exists in Vermont and Oregon. In these states, it is in fact possible for a minor party to cross-nominate a major party candidate, but both party labels are printed on the general election ballot next to the candidate’s name – so there is only one circle on the ballot for that candidate. The minor party is not afforded the opportunity to create a distinct identity and demonstrate its strength (or reveal its weakness) with the voters. Note the difference between Figure 3 and Figure 1. Only in Figure 1 is a voter able to clearly mark which of the nominating parties earned their support.

FIGURE 3: “AGGREGATED” BALLOT ILLUSTRATION

Some observers have attempted to place these two systems as sisters in the same fusion family. But their effects are very different.

The system in Oregon and Vermont[2] is sometimes described as “dual labeling.” It does provide voters with information but it does not allow the minor party the full freedom of association that comes with the opportunity to have its votes (and influence) counted, which is perhaps the essential aspect of a multi-party democracy. Traditional fusion injects countable proportionality into the election results. Dual labeling does not.

One final complication with dual labeling has to do with the requirement in many states that minor parties must cross a “votes received” threshold every two or four years to keep the status of a ballot-qualified party. This is only possible under the traditional fusion system. In dual label states that have a vote threshold test, it is simply not possible to discern whether the minor party has crossed that threshold.

Wikipedia correctly refers to the aggregation practice of Oregon and Vermont as “dual labeling,” distinct from fusion.

“In Oregon and Vermont, a system of dual-labeling exists, which allows a candidate to list multiple party endorsements on a single line, but disallows the traditional fusion system in which a minor party has its own ballot line and votes are tallied by party.”

Wikipedia states even more forcefully: “As of 2022, fusion as conventionally understood by historians and political scientists is fully legal in two states, Connecticut and New York.”

Call “fusion” what it is: separate ballot lines for major and minor parties nominating the same candidate; and don’t confuse it with “dual labeling.” Each is worth understanding, but they are not the same.

Joel Rogers is a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Maresa Strano is Deputy Director of the Political Reform program at New America.

[1] Fusion’s widespread use was facilitated, in part, by the use of separate party ballots.

[2] Dual labeling also occurs intermittently in the few states (MA, NH, PA) that allow “write-in fusion.” Candidates running unopposed are sometimes written-in by a handful of voters, usually though not always from the other major party, and thus end up on the ballot as D-R or R-D candidates.

Fusion voting is stupid and lazy.

Prior to adoption of the Australian Ballot how were the votes by party tabulated?

Sounds like a system to elect communists.

I agree with Fred and Dave.

Jim, good question. I know they were tabulated separately back then because the election returns show they were tabulated separately. For example, in 1856 Millard Fillmore got these votes in Pennsylvania: 55,852 on a Union American ticket, and 26,337 on a Straight American ticket.

That’s nice in theory, but in practice in the state of New York, fusion renders a minor party a vassal of the major party they’re engaging in fusion voting with. Parties like the Working Families Party now have little choice but to run the Democratic Party nominee or risk suffering the same fate as the Green and Libertarian Parties, that is, losing qualified party status and then needing to gather 45,000 valid signatures in six weeks to regain statewide party status (nearly impossible). WFP has no leverage, and parties like the Greens and Libertarians have no ballot line to run their own candidates with.

This is why electoral method reforms, whether it’s fusion or RCV or proportional representation, needs to be paired with fair ballot access requirements.

Fred is stupid and lazy and Dave is probably a fascist.

PR IN ALL REGIMES.

ALL VOTES WOULD COUNT.

—

P-A-T

Stock followed by AZ= convention of the Retard Party. Which one is running for chair?

Thanks for posting this excellent article clarifying fusion and dual labeling voting. The figures shown were useful in understanding the different methods.

Tim; I did not make the above comment. That is an imposter. I have no opinion regarding fusion. I have no opinion regarding Fred or Dave.

I would like to beat the hell out of the person who has claimed to be me for the past several months.

It’s probably Edward Brown. He’s been impersonating Jesus, AZ, Trump, and a whale.

Fusionism is moot with an write-in only ballot. A voter’s preferences are revealed by their choices regardless of how many others may choose. Hence, no laws censoring fusion are needed.

Stock has multiple personalities like Sybill.

REPAIR THE BAN EMAIL SYSTEM RE NAMES TO S-T-O-P IMPOSTERS.

—

HOW MANY GERRYMANDER WINNERS DUE TO 3RD PARTIES / WRITE-INS. SINCE 1776 ???

Edward TJ Brown needs to be sunk below whale poop with all his IMPERSONATION.

17 SEP 1787 –

TOP SECRET FED CONVENTION ENDS.

PROPOSED 1787 USA CONST SENT TO STATES.

1777 ART CONFED IGNORED RE AMDT PROCESS.

DEJA VU REPEAT COMING VERY SOON ??????

—

P-A-T

Biden might try to impose the Chinese Communist constitution making the US a province of Red China.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2023/09/17/trump-capitol-attack-jan-6-supreme-court/70830675007/

Jan. 6 defendants bring cases to Supreme Court. Here’s what it could mean for Donald Trump

The cases are the first to reach the Supreme Court from those involved in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. The outcome could affect the indictment of Donald Trump.

John Fritze

USA TODAY

WASHINGTON − Three men involved in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol are asking the Supreme Court to wipe out part of their indictment − and the possibility of an extra 20 years in prison − in the first criminal cases involving the 2021 insurrection to reach the nation’s highest court.

If the justices agree to hear the appeals, the decisions could ultimately affect part of a federal indictment lodged against former President Donald Trump for his effort to overturn the 2020 election − as well as hundreds of others charged in the deadly riot that unfolded across the street from the Supreme Court more than two years ago.

Edward Lang, Joseph Fischer and Garret Miller claim prosecutors overstepped their authority by charging them with a federal prohibition on obstructing “official proceedings,” a law approved in 2002 in response to the Enron financial meltdown.

Lang documented on social media his participation in the Jan. 6 attack, and Miller gained attention after the riot for threatening Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y.

—-

HOW DOES *SEDITIOUS CONSPIRACY* DIFFER FROM TREASON / INSURRECTION / REBELLION ???

HOW MANY BRAIN DEAD SCOTUS CLERKS – DUE TO SEEING JAN 6 A ZILLION TIMES ???

USSR TODAY AGAIN?!

Fusion voting is important to a functioning, diverse republic. The power of the New York State Conservative Party and Working Families Party due to disaggregated fusion is understated. The Conservative party can cross-endorse a specific Republican (or, rarely, Democrat) candidate and help that person to get the major-party nomination due to the threat that if he or she doesn’t, the Conservative candidate will get enough votes to tip the election (or in very rare cases, win it, such as the late Senator James Buckley and onetime Buffalo Mayor James Griffin.) This is an important factor in ensuring the the major parties offer a real choice and not just two slightly different versions of the same thing.

Standing count by party precludes fusion.

@RW,

See footnote 10 for the 1856 election in Dubin, United States Presidential Elections 1788-1860.

Fremont and Fillmore had a fusion slate of 26 of the 27 elector candidates. Fremont and Fillmore were the 27th elector candidate appearing at the head of the common lists for the the two parties (Republican and American) who distributed separate ballots. The two parties agreed that if the Union slate won they would distribute their electoral votes based on the Fremont/Fillmore split. The top Union elector received 203,534 votes, slightly more than the sum of Fremont as elector 147,286 and Fillmore as elector 55,852 – 203,138.

In any event, the Democratic/Buchanan slate was elected. Had the Union slate received the most votes, then presumably one Buchanan elector would been chosen.

This sounds vaguely similar to the Argentine system. In Argentina, parties may formally join in coalition before the primary. Voters may select a party, which determines the candidates for a close coalition list. So if there were a stoplight coalition, voters could vote for the Red, Yellow, or Green party, and the Stoplight party list would be ordered based on the party votes (D’Hondt allowcation).

The difference between seditious conspiracy and insurrection is like the difference between conspiracy to commit a murder and actually committing one. As it is, it’s an extreme stretch for J6 defendants. They were severely overcharged for what they actually did.

Hunter’s laptop is right. Seditious conspiracy is a ridiculous overcharging. Insurrection or treason would have been even more ludicrous.

https://reason.com/2023/05/08/punishing-rioters-is-wise-bogus-seditious-conspiracy-charges-are-not/

J6 Political Prisoners didn’t do anything wrong!!!

SOME OLDE WHISKEY REBELLION FOLKS IN EARLY 1790S WERE CHARGED WITH TREASON —

NOOOOO MERE INSURRECTION/REBELLION LAW UNTIL 1862 — BIT STRANGE TIME GAP.

They didn’t do anything wrong either. General Washington screwed his troops, and the tax was adding insult to injury. They were fighting for the same reasons as during the revolution. So did our Confederate ancestors and the J6 heroes and political prisoners are continuing that same fight.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whiskey_Rebellion

WIKI

—–

GERRYMANDER MATH FOR 1788-1790-1792 ELECTIONS ???

Free J6 is right about the Whiskey Rebellion.

It’s been… interesting watching Lee Drutman and Steven Hill publicly arguing about this issue. Me, I think Fusion would certainly be a modest step in the right direction in moving alternative parties above spoiler status to having endorsement power that can be traded for policy concessions.

But as I see it, RCV would similarly provide alternative parties with endorsement power but with even more freedom for alternative party voters, who would be free to choose whether or not to follow or flout their party’s suggested ranking.

And of course, Proportional Representation would actually give alternative parties seats and thus more power and influence than either of the above.

God is great, Trump will be President again, and Ukrainian Nazis will lose.